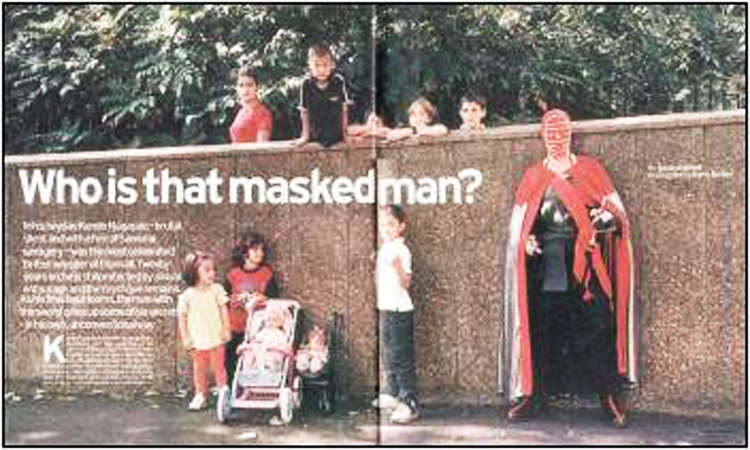

“Who Is That Masked Man?”

“The Observer” Sport Monthly – special article on Kendo Nagasaki

Author of “The Wrestling”, Simon Garfield, pens a stunningly comprehensive article on Kendo for The Observer Magazine. Click on “Continue Reading” below to see the entire extensive article.

In his heyday Kendo Nagasaki – brutal, silent and with a hint of Samurai savagery – was the most celebrated British wrestler of them all. Twenty years on, he is still protected by a loyal entourage and the mystique remains. As his final bout looms, the man with the sword gives up some of his secrets – in his own, unconventional way

Nagasaki, a man who has earned fame by beating other men until they cry for mercy, is walking around Finsbury in north London in search of a place where he can have his photograph taken. He has short brown hair, a narrow face with a prominent and slightly pinched nose, and deeply set eyes that squint in the sunlight. He wears a dark jacket and black trousers, newly shined shoes, a nice fat metallic watch which he consults to find he is a little early. He has three men with him – his manager, his driver, and his website designer. I recognise his manager first, and call out his name: ‘Lloyd!’ At this moment, Kendo takes something from his pocket. It is a soft, worn woollen face mask, black with white vertical stripes, and he pulls it on with alarm. It tightens at the back with those little pop-stoppers you find on baseball caps. He looks menacing, he causes the traffic to slow. On this balmy Wednesday afternoon he believes it is as important as ever to keep up appearances.

Kendo and his friends find the photographer’s studio and move straight for the changing room. This was one of Kendo’s two stipulations: a separate changing area screened by a curtain. The second was a request for photo approval, which might seem a strange demand from a person who wears a mask. ‘He’s not as young as he was, and wants to make sure he looks good,’ his manager explained. ‘He doesn’t want to blow the image at this stage.’ The picture approval was modified to a permission to view the Polaroids.

He emerged from the changing area looking like a man from Japan, only taller. He had a black and gold metal visor, beneath which he had changed the black mask to red. He had a red and silver tunic, red vest and tights, high lace-up boots, a polished breastplate and in padded gloves he held an elegant sword. In truth, it could have been anyone in there, but I knew it was Kendo because he spent the next three hours without speaking a word.

British wrestling was really something in the Seventies and Eighties, though these days one struggles hard to imagine how. Many millions watched it on ITV’s World of Sport on Saturday afternoons, not all of them apoplectic grandmothers. Shopkeepers complained that their customers vanished when the wrestling began at 4pm, and promoters said that the bout before the FA Cup final was seen by more people than the final itself.

A few great characters emerged: Mick McManus, Jackie Pallo, 40-stone Giant Haystacks, Big Daddy, Les ‘Laughing Boy’ Kellett, The Royal Brothers, Peter and Tibor Szakacs, Rollerball Rocco, Adrian Street. Some of these people were so good at their job, so convincing as both athletes and actors, that it was sometimes hard to believe they were faking it. These days it seems preposterous to think of professional wrestling as anything but combative soap opera – even the American executives behind WWF acknowledge this now – but in its British heyday there were a lot of people who were sure that a Boston Crab was the pinnacle of legitimate sporting prowess.

The best wrestlers had a history, or at the very least a story. This being a simple world, the stories were often reduced to the level of a gimmick. Mick McManus didn’t like having his ears messed up and would make his point by moaning ‘Not the ears, not the ears!’ Jim ‘Cry Baby’ Breaks used to throw a tantrum like a two-year-old if things didn’t go his way. A riled Johnny Kwango and Honey Boy Zimba could be guaranteed to headbutt. ‘Ballet Dancer’ Ricki Starr twirled like a dancer. Big Daddy entered to the chant of ‘Easy! Easy!’ Adrian Street, a Welsh womaniser, pretended he was gay. Catweazle wore a brown romper suit and acted like a yokel. Deaf and dumb Alan Kilby always got confused by not hearing the bell. And Dropkick Johnny Peters did something special with his feet.

Kendo Nagasaki emerged fully formed in 1964 with a character so complex that people on the internet are still trying to unravel it today. He liked to portray a broody darkness, as if he had endured a terrible life and was now taking vengeance on all humanity. He liked to hit his opponents with savage force, and refused to take a dive in any of his matches. He had a few specialities – the forearm smash, a rib-crushing rolling finisher – but most of the time he concentrated on submission moves: his opponents did not regard fighting him as easy money. He had strange Samurai rituals, including a salt-throwing routine, and he had half a finger missing from his left hand, which hinted at some cultish and bloody initiation ceremony at the behest of the Yakuza. He also had a flamboyant gay manager called Gorgeous George Gillette, who, when he wasn’t managing the Theatre Royal in Halifax, wore feather boas and sequins, and provided what was called ‘the verbals’. George was needed because the Nagasaki schtick contained two other elements that set him apart from the hoi polloi: he always wore a mask, and he never spoke. This led to a lot of rumours. People said he had been disfigured in a fire; they thought he was another wrestler trying a new image; it was hoped he might be a member of the royal family. As to his silence, it was suggested that he had a voice like a girl.

Kendo, who is now well into his fifties, has decided to take the air. He wanders around the streets of Finsbury in his full regalia, inviting interested stares from passers-by. In a small park, a group of kids just out of school are happy to pose alongside him, but are uncertain who he is. One of them, a boy of about nine, tells me that his uncle ‘could take him anytime – he’s got nun-chucks!’ I tell him that Kendo can be rather brutal, and that he has beaten many uncles senseless, and the kid thought for a minute and then said, ‘Nah!’

Kendo’s entourage are an appealing bunch. Lawrence Stevens, a close personal assistant for a decade, is known as The Man Who Brings the Car Round. Wherever Kendo appears he is often pursued by people wishing to see his face, which means that the wrestler must don the black mask. But he feels awkward travelling the streets in this disguise in search of his transport, and so Lawrence always leaves a few minutes early to bring the transport as close as possible to Kendo. Next up is Rob Cope, a longtime Kendo fan and historian, who works at the Victoria Hall in Staffordshire, the scene of many a Nagasaki triumph. Currently he is also helping the wrestler both with his autobiography and his new internet presence at www.kendonagasaki.com (‘The Official Website of the Master of Mayhem and Mystery’). As we stroll around, Cope and Stevens notice a threadbare patch on Kendo’s silvery robe and tut-tut to each other, rolling their eyes as if to say, ‘That’s going to cost’. And then there is Lloyd Ryan, Kendo’s loquacious manager. Ryan, 55, has provided the goading verbals for a decade, ever since the mysterious death of Gorgeous George. One day Ryan had been watching Kendo fight in Walthamstow when he got called into the dressing room for some important news: Lawrence Stevens said: ‘Look, we’ve got no manager, and we’ve decided that you are going to be the manager.’ The match that evening was against ‘Judo’ Pete Roberts, a hard but unglamorous man from Worcester who wore red swimming trunks, and Ryan was required to hype the match before it began. ‘I went in the ring and spoke a load of crap for 10 minutes,’ he remembers. ‘The crowd started shouting and throwing things, and I thought, “Wow, I could get used to this!”‘

This was not Ryan’s first career. His main claim to fame is that he is the man who taught Phil Collins to drum. Ryan, a north Londoner, discovered drumming while still at school, and claims it is the one thing that kept him out of the hands of the law. He says that his first session sounded like the march on Stalingrad, but he improved enough to join several top cabaret bands. He played with Matt Monroe and P.J. Proby at the Talk of the Town, and went on to teach several notable drummers after Phil Collins, including men from 10CC, Cornershop and Jamiroquai.

In 1975 he enjoyed a near-brush with the pop charts. He was watching the wrestling one day, and thought how much he admired the cruel and savage stylings of Kendo Nagasaki. ‘It’s a brilliant idea – the name, the outfit,’ he remembers thinking. ‘You can’t underestimate the intelligence of someone who put this character together. The one thing I liked about him most was that he was consistent. You never knew anything about him.’

So Ryan and a friend made a record called ‘Kendo’s Theme’ by Lloyd Ryan’s Express. This received an unusually large amount of airplay on several local radio stations, and Nagasaki was so thrilled with it that he agreed to tour the country with Ryan on a promotional drive. Kendo arrived at radio stations in full gear and sat silent and motionless throughout the publicity interviews while Ryan related the anecdote you have just read. ‘It was a sensation for me,’ Ryan says.

For five years, ‘Kendo’s Theme’ accompanied the wrestler into the ring. Eventually, Ryan would give Kendo drumming lessons, and there is a photograph of them drumming side by side, as if they were in Showaddywaddy. ‘If Kendo’s going to play a musical instrument,’ Ryan told me once, ‘it can’t be the violin.’

Ryan seemed to me to be the obvious way to learn more about Nagasaki’s real persona, so a few weeks before the photographic session we struck a deal. He said that Kendo would agree to be interviewed, but only in writing. I would prepare some questions, Ryan would fax them to Kendo’s lair somewhere in the Potteries, and the scales would fall from our eyes. The simplest of plans.

Kendo claims he has never lost a fight, although he hasn’t won them all either. He seems to have been disqualified a lot. His first contest of note came in March 1966 with the defeat of Count Bartelli, at that point one of wrestling’s major attractions. Count Bartelli (real name: Geoff) was also a masked man, but it was a mask Kendo removed one night in Stoke-on-Trent. The Count left the ring with blood streaming from his face to his leotard. The match was talked about for years, and for a while Kendo was judged too vicious for television. His first appearance on World of Sport came in 1971 against Billy Hawes, another momentous tussle. In the next few years Kendo became a regular Saturday fixture, provoking excited comment from commentator Kent Walton. ‘Let’s see if we can get a close-up of him and those red eyes, if you’re lucky enough to be watching on a colour set…’ He appeared regularly before royalty at the Royal Albert Hall (Prince Phillip and the Duke of Kent attended on several occasions), and one particular bout received the detailed attention of Top of the Bill magazine: on 28 May, 1975, ‘masked genius’ Nagasaki defeated Steve Veidor. ‘Veidor gave the masked man a few anxious moments, but after a post-padding had been ripped off, Veidor got into difficulties…’

Kendo Nagasaki appeared on the front cover of TV Times in December 1976, and the fame went to his head. Upset that no one knew what he really looked like, and weary of clinging on to his mask while every opponent tried to remove it, he found a solution: a ceremonial unmasking. One or two people tried to persuade him against this. Max Crabtree, the leading promoter of the day and brother of Big Daddy Shirley Crabtree, believed it was a grave mistake. ‘All that good work that you’ve put in, you’ll lose it all,’ he informed Nagasaki. ‘He didn’t have a very unusual face,’ he told me years later. ‘He was just a nice-looking sort of guy, but nothing significant. But he was so determined to unmask that we decided to do it properly, at the Wolverhampton Civic Hall where he was hottest.’

The film of the evening is a remarkable artefact. Kendo entered a darkened hall with Gorgeous George and several ‘acolytes’ – shaven-headed hangers-on who were introduced as ‘followers of the inner-circle of Nagasaki’. It was five days before Christmas 1977. Gorgeous George took the microphone to dispel rumours that Nagasaki had been injured. In fact, he said, ‘Kendo has been in a secret retreat where he has been learning to build up his powers, his powers not only in wrestling but his powers to help heal other people and to do many other things. Tonight this is the ultimate fulfilment of all those dreams – the unveiling and the unmasking…’ During this speech a member of the Wolverhampton crowd shouted out, ‘Rubbish!’

Then things got serious. Kendo slammed his sword into the centre of the canvas, and knelt as his acolytes launched themselves at his feet. George threw something anointing over his head, and slowly removed the mask to reveal a large star-shaped tattoo on his crown and a long stream of dark hair that resembled a horse’s tail. As George burnt the mask in a metal dish, Nagasaki looked up. People in the crowd gasped. He was a handsome chap after all, aged maybe 30, perhaps a touch Mongolian. He looked a little like Hunter S. Thompson or a mid-period Marlon Brando (not that such comparisons were uppermost in the minds of the Civic Hall crowd). He still didn’t speak, but the stare on his face said, ‘You can see me now, and you still don’t have a clue…’ There was great applause; even his critics were silenced. In the wrestling world, the unmasking was a sensation.

Lloyd Ryan observed the ceremony in London in the company of Diana Dors. ‘We sat in her dressing room, and I persuaded her to watch it. She wasn’t a huge wrestling fan, but I think she came to see its appeal. She said to me, “I thought you were over the top, but look at these people!”‘

The answers came back not by fax but in blue flowery biro. ‘Do you have a family?’ I asked Nagasaki. ‘Any hobbies?’

‘None that I am in regular contact with,’ he replied. ‘Hobbies: boating, horse riding.’ (He also wrote ‘I own a boat…’ but then scribbled it out.)

Q: How do you spend your time these days? A: I divide my time between business activities and leisure pursuits. I am a director of several companies, but do not take part in the day-to-day running.

Q: How would you describe the state of wrestling in the UK today?

A: UK wrestling no longer exists. It’s an abortion of Americanised entertainment. There is no longer any originality, the business does not attract the characters it once did.’

Q: Is there any way back for it?

A: No way back at all. The scene had become stale long before Greg Dyke took it off [in December 1988, when he felt it presented ‘the wrong image’ of ITV to its viewers and advertisers]. The nail in the coffin was the introduction of the US tapes. The whole of the business there is based on comic book creations, everyone has to appear superhuman. The persona of Nagasaki was always greatly theatrical and as such wouldn’t be out of place in the American market, but he is the exception over here.

Q: Can you explain the significance of the salt and the red and black masks?

A: The idea of the salt is a cleansing process, to cleanse the spirit through the contest so that no animosity is felt afterwards. The black mask has become a symbol of meditation for me. I only don the red mask shortly before I enter the ring – it means that Kendo is fully manifested within me.

Q: Your wrestling persona is brutal and unforgiving. Are these traits purely confined to the ring? A: Kendo’s aggression is saved entirely for the ring. There is a period of wind-down following a match when the aggressive nature of Nagasaki is shed and a more harmonious persona is regained.

Q: Inside the ring I do not remember any displays of humour… A: The humour was always in George not in Nagasaki, although it is fair to say that he made me laugh on occasions at his antics. I do enjoy true-to-life humour. I don’t find comedians funny, but something like Willy Russell’s Blood Brothers, despite being ultimately a tragedy, contains the sort of earthy humour that I personally find very funny.

Q: Do you regret the unmasking?

A: I do not regret it, the reaction was very surprising. For many years there had been hatred towards Nagasaki, yet when the mask came off the audience gave me a genuine standing ovation which was quite thrilling.

Q: Would it be fair to say that Kendo Nagasaki’s ring persona is in some way compensating for an unhappy childhood?

A: Yes. My childhood created the need to explore an alternative identity.

Q: How did you lose part of your finger?

A: I offer no explanations or claims, despite various inaccurate explanations offered by some people…

Peter Blake, the painter who has been a Kendo fan since the very beginning, told me he didn’t want to destroy the Nagasaki myth with anything approaching gossip, but said that Kendo is a judoka of world championship class, and certainly did spend some time in Japan. ‘In Japan, [the missing finger] is the sign of a cult, the equivalent of the mafia.’ He said the late photographer Terence Donovan was also a sixth-dan judoka, and that Donovan saw a judo fight in Japan ‘in which a young English wrestler beat the then champion of the world, a Finn. Terence deduced that it must have been Kendo.’

‘The mafia?’ Max Crabtree told me a short while later. ‘Kendo used to be an apprentice at Jennings, the horse-box makers in Crewe. That’s where he got the finger severed off.’ Nagasaki maintains that he would have been just as successful without his mask and myth, because he was such a powerful wrestler. But I doubt this. He fought without the mask on several occasions, but pulled it on again at the end of the Seventies for good. The effect was familiar: people swiftly learnt to hate him again, and to fantasise about who he was. Within a year, no one could remember what he really looked like.

‘He lived in a most beautiful house with about an acre of garden in Wolverhampton,’ Max Crabtree recalled. ‘Worth about £300,000, beautifully furnished. He’d been very lucky. He had an adopted aunt, or she had adopted him, who had a few properties up and down the country, in Blackpool and the Midlands. When she died, Kendo got the lot, which had given him a lot of independence. It’s one of those fairytale stories – we’d all like to have an auntie like that.’ The money came in handy: in the ring he’d be lucky to earn £50 a night.

Crabtree says that Kendo became obsessed about keeping his identity intact, once leaping up in a dressing room to trap a theatre manager’s head in the door, lest he see him without his mask. But very occasionally people did catch him off-guard. ‘So it’s winter,’ Crabtree says at the beginning of his best Kendo anecdote. ‘They have a leak in the bathroom. George, who actually lived with Kendo at this time, looked in the Yellow Pages for a plumber. He finds one, and the guy comes round and George opens the door. I think this is the late Seventies.

‘Now the plumber turns out to be a wrestling nut. Much to the plumber’s amazement, he turns up at this house and there in front of him is his great hero, George Gillette. The plumber doesn’t say anything. So he goes in, and George says, “Peter, the plumber’s here”. The guy reading the newspaper on the couch is Kendo Nagasaki without a mask. The plumber puts two and two together. [He] realises he’s seen the real McCoy, and he’s got the name of the resident of the house – Peter Thornley – because they’d given that to pay for the bill.

‘One night soon after we’re in the Civic Hall, Wolverhampton. Peter’s on the bill and in the dressing room. One of the wrestlers comes lounging in, I think it’s Pat Roach, and says, “Max¿ there’s two fellows at the door giving out these bloody leaflets.” I say, “Let’s have a look,” and it says on it, “The wrestler Kendo Nagasaki is Peter Thornley and he lives at this address¿”

‘I thought, “Them bastards! Where the hell are they?” So I shoot to the front door, and the two guys must have known I had something to do with it, because they throw the leaflets up in the air and go racing down the road. This guy and his friends became a bloody nuisance. Kendo would have murdered the bastard. Killed him. But he couldn’t do, because he had all this heat on him, the star of the show, and he can’t go running down the High Street with his Samurai sword.

‘It didn’t end there. This fellow decided he would invest all of his money not just in printing leaflets. He knew that we advertised in the local paper, the Express and Star. So when the advertisement for a Kendo Nagasaki bout appeared in the paper, underneath it would be a smaller advert that this plumber had paid for: “Please note that the above wrestler, Kendo Nagasaki, is Peter Thornley and lives at this address…”

‘So enough was enough. The plumber ended up in the local magistrates court. We’d got his address and put an injunction on him to stop him from doing it again. He doesn’t turn up at court. He sends a letter in, and says he’s very sorry, it won’t happen again.’

Nagasaki’s career survived the plumber. Indeed, as the appeal and health of his famous adversaries dwindled – Rollerball Rocco retired to Tenerife, Mick McManus retired to Herne Hill, Jackie Pallo had his hips replaced, Haystacks and Big Daddy both became ill and passed away – Kendo maintained his position as the biggest draw in the country.

In 1990 he appeared on a discussion programme on Granada television in which various wrestlers campaigned for a right to have their matches televised again. Inevitably, Kendo just sat there without saying anything, but at the very end of the show he became annoyed with one of the other wrestlers and began throwing him around. This was a pre-arranged scuffle, but it was news to a female make-up artist standing nearby. This woman, who had been Sir Laurence Olivier’s personal make-up artist for several years, hit her head against the wall, was briefly unconscious, and woke up in terrible pain. The accident ended her career. Shortly afterwards, the broadcasting workers’ union Bectu decided to sue Granada and Nagasaki on her behalf. The case lasted seven years. Granada attempted to shift all responsibility towards Nagasaki, who was not insured. But the judge ruled that Nagasaki had only been doing what he was told, and ordered Granada to pay the make-up artist compensation of £327,000 plus costs.

Q: What can you tell me about your involvement with the healing arts?

A: I very seldom practice my healing techniques these days. For a time my work in this field was very successful. I don’t these days have a healing clinic, although I’m pleased to say there is a long list of people who have testified to my abilities in this area.

Q: How would you sum up your experience of managing rock bands? [In the Eighties, Nagasaki and Gillette guided the career of the Cuddly Toys, among others).

A: Rock is a very cut-throat industry, but I had a lot of fun. Had it not been for George’s illness, I would probably have stayed in the field a little longer.

Q: What are your thoughts on the euro?

A: Entry into the European Community does generally seem to me to be a good idea, so I would support adoption of the euro. I would like Kenneth Clarke as the next leader of the Conservative party.

Q: How would you like to be remembered?

A: As British wrestling’s greatest masked wrestler. Having been voted Wrestler of the Millennium by the fans recently it would seem I have achieved that goal. Peter Blake’s portrait has also added to a certain immortality.

The friendship between Peter Blake and Kendo Nagasaki came about in an unlikely way. Blake was once asked by a magazine what he would have liked to have been had he not been an artist, and he said a wrestler, and more specifically Kendo Nagasaki. (In the same feature, Nagasaki said he wanted to be Richard Branson, because ‘he’s not one of those faceless magnates who hides behind the frosted windows of a limousine’.)

Kendo agreed to sit for a Blake portrait for the BBC Arena programme, ‘Masters of the Canvas’. They struck up a rapport, and the two now frequently share a meal together. Between mounting shows at the Royal Academy, Blake even helps out during Kendo’s increasingly rare appearances in the ring. ‘A few months ago I agreed to appear with him at a charity show he was doing for the mentally handicapped,’ Blake said. ‘I was introduced in the normal way – you know, the man who did the Sgt Pepper album, – and the person who presented me was very impressed that I’d got a CBE. Then there was the normal shenanigans with Lloyd Ryan. He said to me, “Call yourself a painter? I wouldn’t let you paint my bathroom.” It was a lot of fun.’ The friends met up again in the summer, at the opening of a new exhibition at Agnew’s art gallery in Old Bond Street. A young artist called Peter Lloyd had made a series of prints about masked Mexican wrestlers, and Nagasaki and Blake found them hard to resist. Over drinks and nibbles, Mark Adams, Agnew’s director of contemporary art, introduced Kendo as the guest of honour, and the wrestler stood around in full visor and cape looking serene. The partygoers were blasé, as if Nagasaki was just the latest type of stripogram.

‘Kendo got a bang on the head last week because someone ran into the back of his boat,’ Peter Blake told me. ‘So now his jaw is all hurt and he can hardly talk even if he wants to.’ Blake calls Kendo Peter when he doesn’t have the mask on, but never when he’s in character. ‘He needs a good period of silent meditation to become Kendo. It’s not like a light bulb you can just switch on and off. He treats Kendo as a separate entity and talks of him sometimes in the third person.’

Blake is a little sad that the wrestling is over. He says that 20 years ago Kendo could have gone to the States and ‘wiped them all out,’ but he now has a slight heart complaint and such ambitions are over. Nagasaki has one more big wrestling date in his diary, a tag-team match at the Victoria Hall, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, on 22 December, after which his doctor has advised him to hang up his mask for good. ‘There is a mystery about the Peter Thornley story as well,’ Blake adds, ‘like who his parents were.’ He looks up from his white wine. ‘But I think it’s important that we retain at least a part of the mystique.’

As we are talking, Kendo decides it is time to leave. He exits the gallery looking smart but casual, the way a man in an elegant shirt and black striped mask is prone to do. Lawrence brings the car round, a bottle-green Rover Vitesse, and Nagasaki manoeuvres himself into the passenger seat. They head down Old Bond Street, left into Piccadilly, and it is not until they have passed the Royal Academy that Kendo decides it is safe to remove the disguise. They are heading back to the boat in Brighton for a spot of fairweather sailing, and by the time they reach the coast, the world where a nine-fingered English businessman may dress as a Samurai warrior and administer savage beatings will be far behind. I imagine.